"Music should be the most individualistic form of expression."

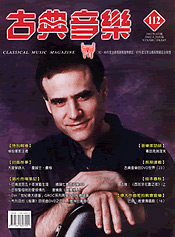

When the name James Kreger is mentioned, not many people here would have heard about him. His performances are mostly on the east coast of the United States and in Europe. Although he is winner of the Tchaikovsky International Competition and Piatigorsky Prize, has also released many CD's which have received excellent reviews, including CBS/Sony, Melodiya, Koch, and has appeared numerous times on United States PBS and Japanese NHK Networks, his fame on the world musical stage in no way matches his artistic achievements. Why has it happened like this? We can find some answers through this personal interview with Kreger.

James Kreger was born on March 30, 1947, in Nashville, Tennessee. When he was about seven years old, Kreger was mesmerized by the art of classical music when he first heard a recording of Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony in Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. According to Kreger, the instruments he really wanted to learn at that time were the saxophone and the piano, but the former was not available at his school, so he settled for the cello instead. He showed early talent both in his understanding of music and his technique, and in 1966 he won the Piatigorsky Prize at age 18. In 1974, amidst fierce competiton, he won a major prize at the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow. In 1971 Kreger made his debut at New York's Carnegie Hall, in a program including the Tartini Adagio, Franck Sonata, Chopin Introduction and Polonaise Brillante, Schumann Adagio and Allegro, and a new work by Jeff Jones, all of which served to demonstrate the essence and power of his performances to the whole world. The New York Times gave him an excellent headline review, praising his playing as combining the best qualities of Rostropovich and du Pre. Kreger's superlative technique, always at the service of the music, and his glorious tone, prompted The New York Times to account this recital "a memorable event." At the time Kreger was still studying under Leonard Rose and Harvey Shapiro at the Juilliard School. Subsequently, he graduated with the school's highest honors, winning both the Morris Loeb Award and the Felix Salmond Prize.

Unlike most of the world-class musicians today, Kreger tends to keep a remarkably low profile. He demands of himself the highest level of artistic quality, and he does not agree with the high-powered commercial approach to classical music marketing, which tends to standardize everything in the public perception. He deeply believes that a musician's "voice" is his/her personal trademark and soul. In this age of mass communication, it's possible that the styles of others and the environment of one's upbringing can influence one's musical interpretation, but ultimately, one has to trust one's own music. Because of this, Kreger has been recognized by many critics as special and unique in his age, one of the most individual and subtle of his peers.

From talking to Kreger, you can sense that he's a romantic at heart. He describes his music as an infinite emotional outpouring. "The aim is to match one's technique to the intensity of the music, and hope to enter the composer's special world by ‘becoming' the music." Kreger thinks the cello is the instrument that most closely resembles the human voice: "It can sing, talk, and even speak verse as in a Shakespearean play." Having heard him say this, I can understand the special quality that Kreger brings to the post-romantic repertory and how its musical nuances particularly suit his interpretative style.

The three recordings below, representing very different works in the 19th century romantic era, were written by Mendelssohn, the ultimate romantic, Dvořák, a romantic heavily influenced by the folk idiom, and the more dramatic Strauss. Through these marvelous performances we can clearly experience how Kreger immerses himself in the music, where he is transported into the pure and refined musical world, or taken on to the heroic stage (Don Quixote), where we are challenged by the windmills.

This CD is a collection of two cello sonatas, Op. 45 and Op. 58, the Variations, Op. 17, and the Song Without Words, Op. 109. Mendelssohn's cello sonatas are the most important pieces of music for cello after Beethoven. It is well known that Mendelssohn was a child prodigy on the level of Mozart. In 1836 he wrote his friend Hiller indicating that although composing music for the piano came easy to him, this didn't give him the most joy and sense of achievement. He needed another medium for his emotional fulfillment and creativity, and he found great happiness writing trios, quartets, and other compositions with string instruments. This was why he started work on his cello sonatas.

On October 13,1838 he completed his first cello sonata. At that time Mendelssohn had just recovered from the pain and suffering of measles, and one can sense this welcome news from the music. The essence of the opening movement was best described by Schumann: "This is a constantly smiling artist, showing the joy he achieves from his art, and complete fulfillment in his personal world." Five years later, in 1843, Mendelssohn completed his 2nd Sonata, Op. 58, and gave the first performance with Carl Wittmann on November 18th. At the time Mendelssohn was constantly commuting between Berlin and Leipzig and was under a great deal of physical and emotional pressure. The tolls of daily life are truthfully reflected in this very different work. Consisting of four movements, the feel of the music is totally unlike the first sonata.

The first solo cello piece by Mendelssohn was the Op. 17 Variations, which he completed on January 30, 1829. He wrote this music for his brother Paul. The theme and six variations each build up with a cumulative effect to achieve the full intensity of the score.

This Mendelssohn recording is perhaps Kreger's most distinguished, receiving a best recommendation from the editor of this magazine in 1999, and it was equally well-received by critics throughout the world. The recording is utterly inspiring and can be easily recommended as the standard of reference in an under-recorded repertory. Kreger uses his considerable technique and power of interpretation to bring out the diversity in Mendelssohn's genius through these four very different works. Otherwise, the life of the music could easily have slipped through the fingers of a lesser performer. Kreger's judicious use of vibrato perfectly complements the delicate and subtle tonal colors of Mendelssohn's score. Even in as romantic a piece as Song Without Words, Kreger does not let an overuse of vibrato and energetic bowing draw attention to itself. The peaceful and tranquil mood he maintains throughout makes this performance a complete winner.

Kreger is partnered on the piano by the 1969 prize winner in the Van Cliburn Competition, Gerald Robbins. A well accomplished soloist, Robbins plays chamber music regularly and has collaborated with Milstein, Zukerman, Kyung Wha Chung, and Ricci. Through his rich experience in playing alongside string instruments, he is able to achieve a particular rapport with Kreger. The way the two instruments breathe together and yet are able to show their contrasts must be accounted a model of chamber music performance. The genius of their interpretation enables the listener to fully appreciate the very different styles of the two sonatas, reaching right into the mind of the composer over this stage of his life. The success of a recording depends upon its performers, and it's obvious that the time that Kreger and Robbins must have spent on studying the music and the very deep communication they achieved have resulted in a wonderful recording.

In addition to Dvořák's Cello Concerto in B Minor, this CD also includes his Klid ("Silent Woods"), and Victor Herbert's 2nd Cello Concerto in E Minor, both seldom performed and mesmerizing works, and both associated with the birth of Dvořák's Cello Concerto. Victor Herbert was born in Dublin in 1859. When he was three his widowed mother took him to England. Later they moved to Stuttgart, Germany with his stepfather. He completed his musical education there and later became active in the European musical world as a cellist and composer. In 1886 both Herbert and his soprano wife were engaged by New York's Metropolitan Opera. In 1892, when Dvořák arrived in New York, Herbert had already left the Metropolitan Opera and had become associate conductor of the New York Philharmonic. On March 9, 1894 Herbert's own performance of his 2nd Cello Concerto was a great success, and it changed Dvořák's conception of the cello as a solo instrument. Dvořák began writing his own cello concerto in November of that year.

Almost all of the world's most famous cellists have recorded the Dvořák Concerto. So has Kreger. However, in this fiercely competitive recordings market, an artist must bring something very special in order to attract the buying public.

Although this recording has the added interest of the two novelty pieces, it must still be judged on Dvořák's concerto. Kreger surprises by harnessing the emotional explosiveness the score can bring, and through a very integrated approach, which at the same time brings out the continuity and contrasts of the various movements, enables the listener to experience the wholeness of the piece. Because of this one has to listen to the concerto at one sitting in order to appreciate Kreger's vision and the power of his performance.

Ever since Cervantes' Don Quixote was published in 1605, it has inspired a number of composers, including Richard Strauss, Massenet, and Weber. Strauss completed his tone poem on December 29, 1897. Besides using the cello to depict the protagonist, Don Quixote, Strauss delegated the role of the servant Sancho Panza to the viola, and Dulcinea, to the violin. Though partly a triple concerto, the dominance of the cello makes this an important piece for the cellist as soloist, and because of this, Don Quixote has entered the standard solo cello repertoire.

Compared to the other two recordings, the orchestra is far more important here. Although Strauss has already defined the cello's role, it is a difficult task for the cellist, conductor, and orchestra to fuse together in a convincing manner. This is the most successful aspect of Kreger's performance: he puts himself into the character of Don Quixote by virtually becoming the role, rather than merely acting it, and while he remains the main character, the soloist, in the story, he can still play as part of the orchestra rather than as an elevated soloist sitting beside the conductor, thus maintaining a marvelous dialogue with the other members. This is especially apparent in the variations where Kreger is just conversing with the orchestra in telling the age-old story and thereby achieving a fully integrated interpretation of the piece. Consequently, whether or not the cello or the orchestra is the main role no longer matters, since they both merge into each other completing the whole. In other recordings of this work the cellist can appear over-dominant, but Kreger and Korean conductor Djong Yu have shown a completely new and to me more satisfying model.![]()

Translation: Hsing-Lih Chou